British director Ben Wheatley’s movie ‘A Field in England’ is a baffling but brilliant occult classic. The entire piece is allegorical, thick with symbolism. The challenge (and the fun) lies in interpreting those symbols in order to get to the heart of the film’s meaning.

First, a very brief summary of the plot: set in the English Civil War, Whitehead is a neophyte astrologer sent by his master to arrest O’Neil, an alchemist, who has stolen certain rare documents. Accompanied by two army deserters, he becomes embroiled in the alchemist’s obsession with locating a valuable treasure buried somewhere in a field in England.

The movie is an allegory, a dark parable. It depicts the alchemical process as a metaphor for personal ‘transmutation’, yet is a commentary on the Civil War itself. Mid 17th century England was a country on the cusp; superstition, magick, folk practices and religion intersected with an emerging Age of Reason, science, constitutional, social and religious upheaval. The movie reflects these strange juxtapositions.

It begins with Whitehead stumbling through a hedge into the titular field. He is a self-confessed coward, a clerk, a student of the esoteric arts and an ‘homunculus’ – a man only partially-formed. One of the movie’s themes is servitude – enslavement to ignorance and authority – versus freedom through enlightenment; in other words, the movie charts the alchemical process of transmutation from ignorance to illumination. Whitehead is beholden to his master and so not in control of his own fate; he is, in this sense, an incomplete man; a ‘stranger to the world and to himself.’

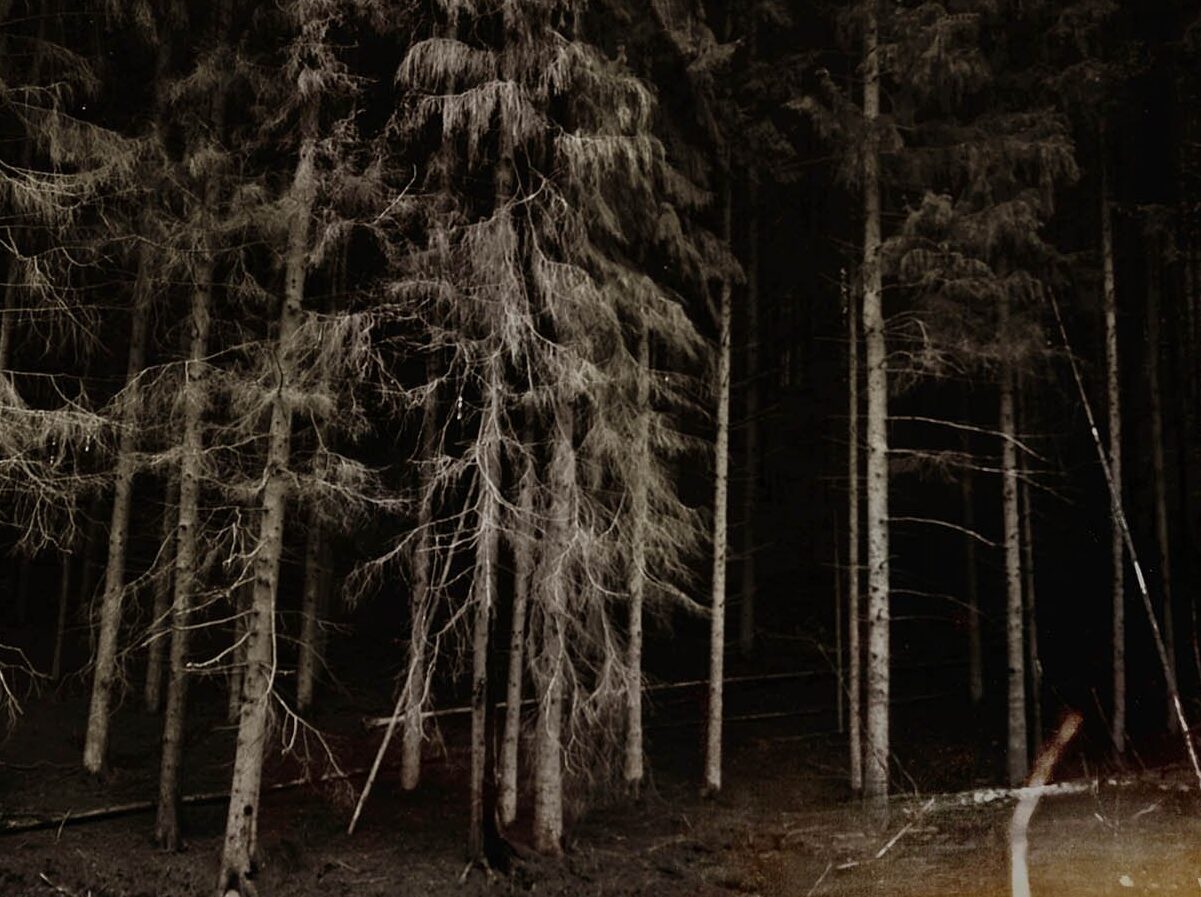

On the other side of the hedge he encounters more protagonists: Cutler, the alchemist’s servant, and Jacob and Friend – two deserters. The field is immediately marked as a liminal and magickal place where different rules apply. In English folklore, hedges are not just physical boundaries but borders between worlds. By passing through, the characters ‘cross over’ to a place where access to the otherworld is possible. This is why Friend and Jacob appear to wake up (from the sleep of ignorance and mundane existence) and why Whitehead says he sees ‘only shadows’ this side of the hedge. Cutler adds to this, claiming ‘you’re as good as dead to them this side of the hedgerow’ and reminds Whitehead ‘they’re only shadows here.’ The implication is that everyone has been intentionally conjured into the field by the alchemist, rather than coming together accidentally via the ‘alchemy of circumstance’.

Whitehead’s magickal credentials are confirmed when he explains to Friend how he enjoyed access to his master’s library, in order to study astrology, prediction, divination and prophesy (the ‘natural philosophers’ of the 17th century dabbled in the occult, but were nevertheless at the vanguard of Enlightenment thought.) Friend, who admits he has never looked up at the stars, seems to wallow in his ignorance; he has ‘air between his ears’. Servile and unenlightened, he both expects and fears suffering and punishment. Whitehead sums up Friend’s persecution-complex when he says ‘whilst we live in fear of Hell, we have it.’ And although Jacob delights in ‘no more orders’, his constant assertion that he is ‘his own man’ rings hollow. Neither of them are truly (yet) masters of their own destinies.

Cutler leads the others to his camp and feeds Friend and Jacob mushroom broth. Whitehead refuses. He ‘does not suffer the same hunger’ as the others. The stew marks those who drink it, in much the same way as the rabbit in Wheatley’s ‘Kill List’. Here though, through weak-mindedness and the desire to fulfil their base appetites, Friend and Jacob become servile once more; the mushrooms bind them to the service of the alchemist. Whitehead, a man of loftier aspirations, avoids the alchemist’s trap; unlike the others, his goal is to achieve mastery over himself and the tools of his magickal trade – and ultimately become a ‘whole man.’

Cutler orders Jacob and Friend (and Whitehead – at musket-point) to heave a rope; attached at the far end is the alchemist, stripped to his underwear. It appears as though he has been pulled out of a distant hedge, or a mushroom circle, suggesting O’Neill had entered another realm. In certain cultures shamans were attached to ropes prior to their descent into the otherworld, to enable their later retrieval. In English folklore, mushroom rings are portals to the otherworld; exit from them is not easy however; rope rescue is one method, another is using a rowan branch to break the circle.

The alchemist is ‘returned’ by the co-operation of the others, but this is only achieved through deceit and cunning, rather than honest means. A rune stone lying amongst the mushrooms is indicative of discarded or hidden knowledge. We might suppose that O’Neill beats Cutler because his withdrawal from the otherworld interrupts his quest for supernatural knowledge of the treasure’s location.

O’Neill is dressed by his servant, confirming Cutler’s servile status. The alchemist asks for his scrying mirror – an obsidian disk used to communicate with spirits. It is reminiscent of a similar object used by Edward Kelly, Dr John Dee’s companion, to document the angelic Enochian language. O’Neill’s mirror likely has a more malefic purpose; Whitehead observes that the alchemist has ‘passed all bounds of Christianity’ in his vain attempts to find the treasure.

The extent of O’Neill’s camp suggests he has been a resident of the field for some time. Despite his attempts to access the otherworld and converse with its denizens, he confesses to ‘little success in applying the master’s arts’. Whitehead and O’Neill share the same master, but they are opposed in thought and deed. O’Neill is worldly; he has branched out on his own, claiming to be his own man, but in reality he in a slave to the promise of wealth, making him greedy, unscrupulous and devious. As a consequence of his misdirected energies, focusing on material wealth instead of spiritual concerns, his occult skills are poor. In contrast, Whitehead remains a servant to his master, is naïve, pious and kind, and so possesses a ‘keener’ occult eye; his gifts are ‘stronger in certain areas’. O’Neill conjured Whitehead to the field to exploit his knowledge and innate abilities, to aid his pursuit of the treasure. In this era there was no conflict between the pursuit of both high magick, which Whitehead calls ‘a holy quest’, and the Christian faith (at least amongst learned gentlemen; an old woman practicing herbalism and folk magick would likely suffer a far worse fate however.) Properly directed by a moral practitioner, natural magick was a path to redemption. O’Neill, by contrast, appears to have taken the left-hand path. His motives are selfish, and he is ultimately doomed.

In one of the films most unsettling scenes, O’Neill ushers Whitehead into his tent. The events that take place inside are not revealed, but Whitehead’s screams are heard. He then emerges, deranged and grinning, bound with rope; in this state he leads the alchemist to the supposed site of the buried treasure. We are perhaps to assume that Whitehead is a victim of possession, in the thrall of an otherworldly creature perhaps summoned via the Master’s black magick. Whitehead is the vessel for this infernal intelligence, brought forth to dowse for the treasure’s true location. The scene also recalls an initiatory process: secrets have been revealed to the unworldly Whitehead; they provide him with a heightened insight into the true nature of things.

The alchemist forces Whitehead to drink, thereby breaking his oath of abstinence. Whitehead then coughs up a number of rune stones; in so doing, he ‘gives up’ the secrets of his arte to O’Neill. But the alchemist has no true insight; he does not understand the runes and so goes to consult the forbidden papers stolen from his old master.

Friend and Jacob, still enslaved to the alchemist, are press-ganged into digging for the treasure. But there is nothing at the bottom of the hole, only death in the form of a skull. This recalls the moral of Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale: the love of money is the root of all evil. The real treasure is the growing fraternal bond between Whitehead, Friend and Jacob; they increasingly help one another, ultimately working together to defeat O’Neill. This evolving brotherly love echoes the alchemical process, the transmutation of an individual into a complete person, pure of soul and spiritually liberated. As Whitehead says, ‘the treasure is here, between us.’ This transformation is lost on O’Neill and Cutler, who see others as nothing more than tools to achieve their selfish ends. O’Neill sums this up when he says to Cutler ‘dying is the only way out for you.’ The fraternal impulse speaks to motives behind the English Civil War, one of which was the desire to create a new order, one defined by equality, brotherhood and freedom from royal tyranny. It is also redolent of Freemasonry; some believe Cromwell was a Mason, and the Civil War was actually initiated by Masons who sought to further their agenda.

The recurring motif of the ‘black sun’ can be explained as the eye of God; it resembles O’Neill’s scrying mirror, which is used to discover the secrets of the spiritual realms. In Renaissance astrology, the celestial bodies were considered channels through which God’s power flowed. The ‘black sun’ may also indicate a solar eclipse, which was recorded as occurring during a Civil War battle, and was one of the era’s many ominous signs and portents. In relation to the alchemical maxim ‘as above, so below’, an eclipse would carry weighty symbolism, perhaps signaling change and upheaval. This is reflected in O’Neill’s comments that ‘the world is turned upside down’ and ‘this country is on the edge of something.’

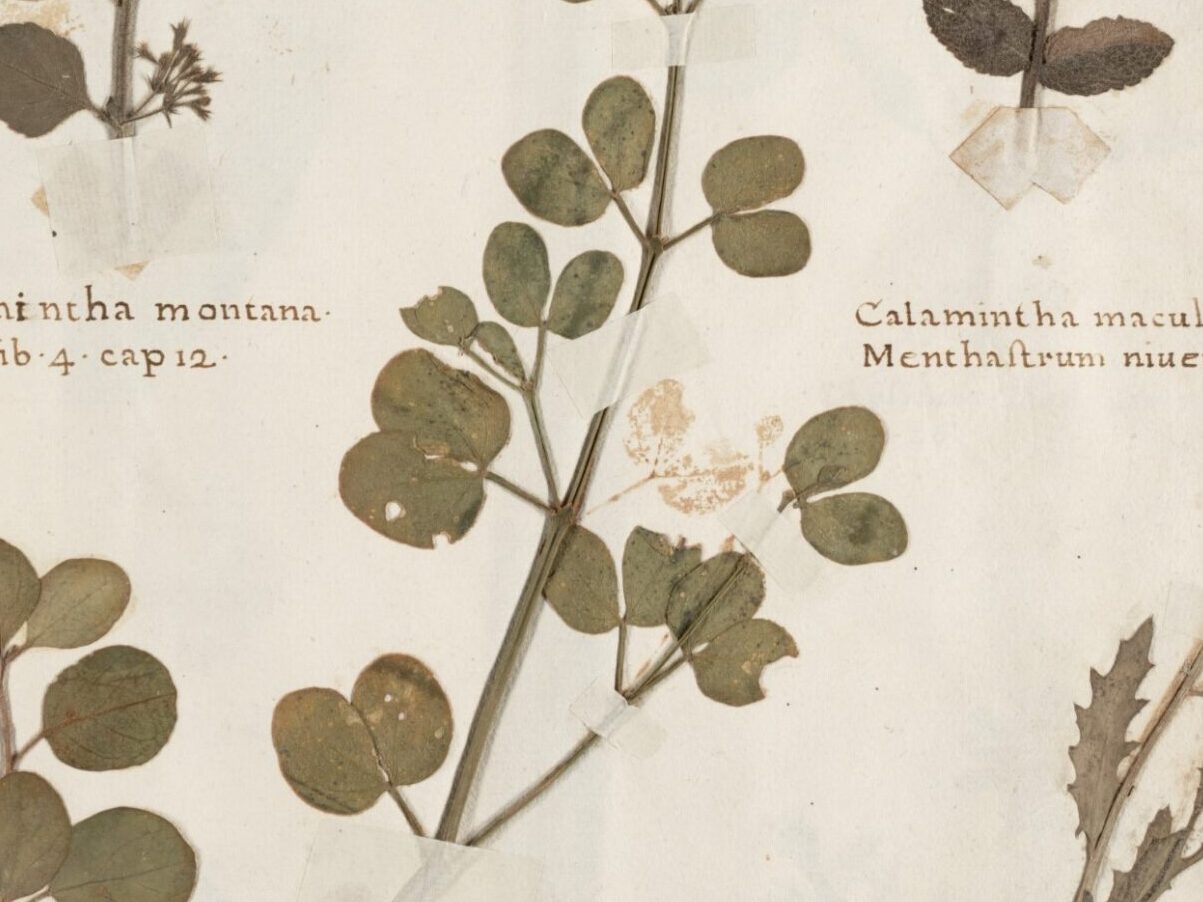

Jacob, who has been growing ill throughout, is revealed as being riddled with disease. Whitehead uses his knowledge to make a poultice, which ultimately cures him. Whitehead then performs another good deed. Cutler, seemingly by accident, shoots Friend. Jacob asks ‘can you do something?’ and Whitehead prays, but with a new intensity. Later, Friend is miraculously restored to life, through the power of Whitehead’s arte. More deaths follow: Cutler, Jacob and Friend are shot by O’Neill. Cutler’s death appears to be directed by Whitehead, using his magickal will to influence the alchemist. Jacob and Friend are killed in their service to Whitehead, honouring their bonds of friendship.

Whitehead’s penultimate act is to eat the mushrooms. In doing so he breaks his oath to his master but, in turn, becomes free of the bonds of servitude. ‘I am my own master’ he declares. He is no longer a coward or an homunculus; he has become a complete man. O’Neill’s power is also shattered; his scrying mirror, symbolic of his control over the protagonists, is broken in two. Fully transformed, Whitehead declares to O’Neill his new mission: to ‘chew up all the ill intentions inflicted by men like you onto men like me.’ Again, this statement reflects the wider concerns of the English Civil War. O’Neill, already compared to the king, is about to be defeated by a new brotherhood; it signals the end of tyrannical single rule and the beginning of a new order; a wind of change blows through the field.

O’Neill appeals to Whitehead’s fraternal instinct, claiming ‘we are now brothers.’ But Whitehead shoots the alchemist, a final necessary act. He joins the two pieces of the broken scrying mirror and holds them to the sky, recalling the image of the ‘black sun’, symbolizing his destiny fulfilled. Jacob and Friend are given a Christian burial. Whitehead collects the documents stolen by O’Neill, abandons all his weapons, then leaves and passes back through the hedge to the world of mundane reality. There he encounters Jacob and Friend, alive and whole. In subscribing to the new model of fraternal cooperation, they too have undergone an alchemical transformation.

Redeemed by their selfless actions, their reward is escape from the field; they return to the world as men of wisdom and self-control. In contrast, the tyrannical old order of O’Neill and Cutler remains dead or trapped in the netherworld of the field. They have learned nothing and remain unenlightened. They are the ill fortune that, in the words of Whitehead, is ‘buried in the belly of this place.’