Nemglan (pronounced NˠEV-ɣlən or something like ‘Nyevghlunn’) is an enigmatic, indistinct figure in Celtic myth. Even his name is ambivalent: it can be interpreted as ‘pure radiance’ or ‘unclean’. A shapeshifter, god of the birds, a king, a warrior and rule-giver to sacral kings, he is one of the Tuatha Dé Danann – powerful deities who inhabited both the physical world and the otherworld before the arrival of humankind. Early Christian writers identified them as fallen angels.

Nemglan is introduced in the tale Togail Bruidne Dá Derga. Conaire Mor is a legendary High King of Ireland, conceived when his mother is visited by a being (probably a deity and possibly Nemglan) who flies in through her skylight in the form of a bird. Conaire is brought up as the son of Eterscél, a human king. Given the Celtic Christian perception of Danann as fallen angels, it is possible to consider Conaire as a variant of the Biblical Nephilim.

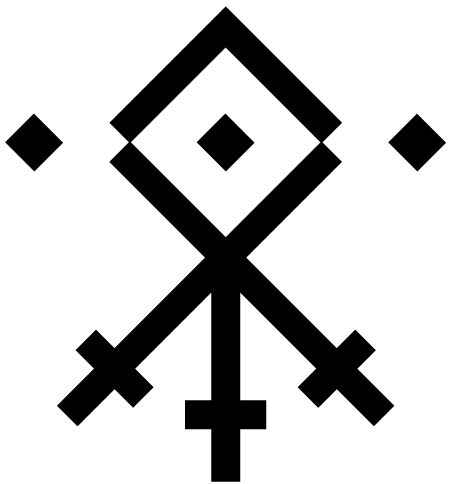

Prior to his own ascent to the throne, Conaire pursues a flock of birds who turn out to be otherworldly bird-men. Armed with spear and sword, they are poised to kill Conaire when their king – Nemglan – protects him. Nemglan reveals Conaire’s true provenance and imposes eight gessi – taboos – upon his reign. These gessi represent Conaire’s contract with the otherworld; if he keeps the prohibitions, his kingship and the land will prosper.

These binding injunctions are a key component of sacral kingship, where the regent is a conduit for divine energies, the binding link between earth and sky, upper and lower worlds. Through his gessi and correct deportment – including the enacting of the appropriate seasonal rites and exhibiting ‘true speech’ – the sacral king was responsible for the flourishing of nature and the beneficent action of the elements. In some traditions the regent performed a kind of heiros gamos – a magickal rite marrying male and female, the king and his land, the sun god and the earth mother. There is evidence of sacral kingship active in early Anglo-Saxon and Norse traditions, as well as Celtic society (not to mention the kings of ancient history.)

In the case of the unfortunate Conaire Mor, Togail Bruidne Dá Derga charts his descent towards death as he is forced through circumstances to break one after another of the taboos given to him by Nemglan. In contrast, Nemglan himself is described as an exemplary ruler, his reign unparalleled in prosperity.

Nemglan’s status as god of the birds is significant. In Celtic tradition (and many others) birds are otherworldly creatures; in some cases psychopomps and spirit guides, in others messengers of the gods, or even souls of the dead. The shape-shifting transformation from human to bird – a common motif in Celtic myth – represents the liminal state of the soul; it is located neither within a human body or the unseen realms.

In the early Irish text known as Sanas Cormaic this human-bird transformation extends into the shamanic realm. It mentions a garment known as a tuigen (also known as an énchennach), a covering or cloak made from white and multicoloured feathers. Only master poets or bards – one of three categories of Druid – were permitted to wear it. The wearing of feathers is a sign of avian kinship, magical ability and poetic inspiration. A similar cloak was worn by the Druid Mug Roith; by reciting magical rhetoric, he was able to fly and then descend back to earth. The legendary 7th century poet Senchan Torpeist also wore a cloak of feathers.

Similarities can be found in Norse tradition. The text of Thrymskvida, reveals how the goddess Freyja – associated with the shamanic sorcery known as seiðr – donated her hawk feather cloak to Loki:

Then Loki flew, and the feather-cloak whirred,

Until he passed beyond the borders of the gods,

And passed into the Giants’ Domain.

The feather cloak is a recurring motif in shamanic lore. As part of a complex symbolism, its existence relates to the idea of the eagle as father to the first shaman and the notion of magical flight to the centre of the world – the world tree. This symbolism relating to eagles and ecstatic flight is found ‘more or less all over the world, precisely in connection with shamans, sorcerers, and the mythical beings that the latter sometimes personify.’

In their role as prognosticators and divine messengers in Celtic myth, birds traverse the permeable boundary between physical and non-physical worlds, the soul and the body. They are associated with the carriage of speech and poetic inspiration – literally winged words. In divination rituals, paths of flight indicated supernatural directives; the future was frequently divined from from the cries of the raven.

Poetry was considered the truest form of speech, related to truth, authority and kingly judgement; its origins were divine (one of Plato’s four ‘manias’ – possession or inspiration from the gods – was poetry.) Thus, an essential skill for poets and kings alike was the ability to speak the language of birds – it unlocked poetic inspiration, otherworldly communication and augury. It was typically an aristocratic skill, achieved through magical initiations. Sigurd in Norse myth, for example, drank the blood of Fafnir the dragon and thereafter understood bird-speech.

Nemglan then is a powerful ally for anyone engaged in esoteric poesis. As king of birds he can be called upon to grant ornithomantic wisdom. He may reveal the language of birds and, in turn, impart poetic inspiration – an in-pouring of supernatural currents – giving rise to the pure and true speech of the spell-weaver / story-teller. As an avian shape-shifter and ‘wearer of feathers’ he is a gateway between realms, a spirit guide in the otherworld and a master of the ecstatic flight of the shaman-poet-sorcerer. As giver-of-taboos he may set prohibitions that, if observed, can yield self-knowledge and gnosis.

Swan-spell,

Raven knell;

Telestic words:

The language of birds.

Bibliography:

Eliade, Mircea: Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (Arcana 1989 ed)

Enright, Michael J: The Sutton Hoo Sceptre and the Roots of Celtic Kingship Theory

MacLeod, Sharon Paice: Celtic Myth and Religion (2012)

O’Connor, Ralph: The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel: Kingship and Narrative Artistry in a Medieval Irish Saga (2013)

Orchard, Andy (trans): The Elder Edda (2013)

Ross, Anne: Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition (1967)

Slavin, Bridgette: The Irish Birdman: Kingship and Liminality in Buile Suibhne; Text and Transmission in Medieval Europe (2008)