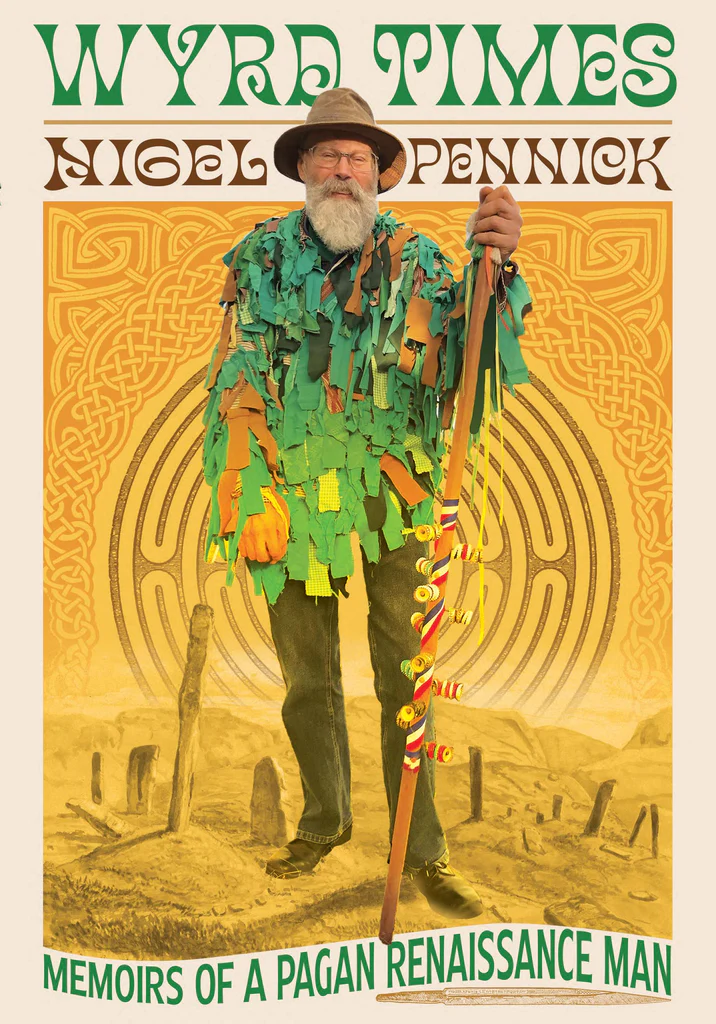

By his own admission, Nigel Pennick is a sceptic, in the sense of someone who questions claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. It is a trait that appears to have shaped his life to a lesser or greater extent, from his childhood rejection of organised religion – specifically the Christian Church – to a final assertion at the book’s conclusion, that one should be free to amend one’s beliefs throughout a lifetime, according to the evolution of one’s understanding of the meaning and purpose of life, and the wisdom imparted by it over time.

Conversely, certain phenomena exerted an unequivocal impact on Pennick, such that all scepticism was immediately exorcised. These include a profound and long-lasting affinity with Old Norse and pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon spirituality, and certain powerful visionary experiences that further shaped his worldview. This bedrock of certainty, leavened with a healthy dose of scepticism and non-conformism, have directed his efforts over the decades, resulting in a legacy that is genuinely unique.

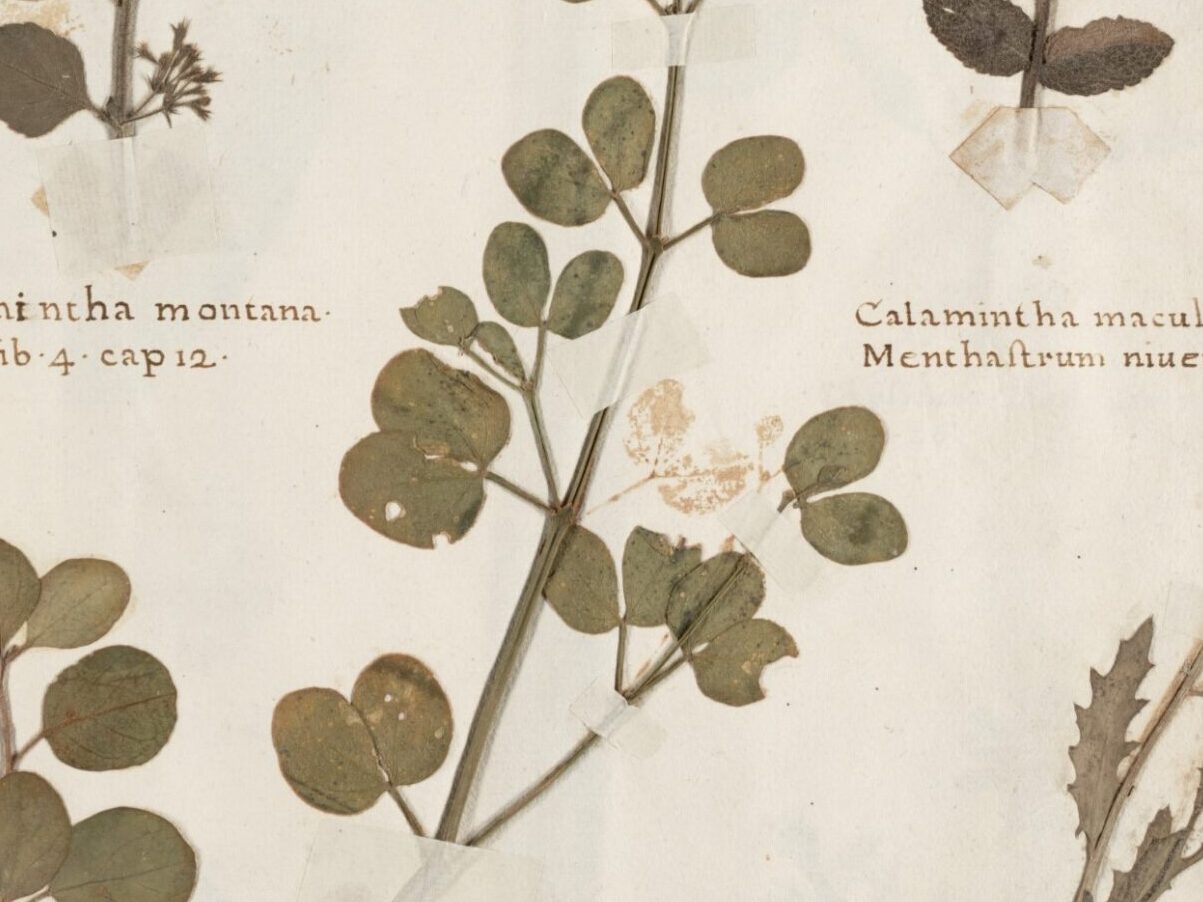

The book tackles various aspects of his life chronologically, while revisiting certain dates and events from alternate perspectives, sometime more than once. The first chapter focuses on his early years: his childhood in postwar London, the privations of a brutally disciplinarian state education system, and his love of Arsenal FC. Thence to Cambridge in the 1960s as a botany and zoology student at the Cambridgeshire College of Arts and Technology. As one might expect, these student years were pivotal in the development of Pennick’s later preoccupations. Student activism, agitprop-publishing, the flowering of alternate cultures and nonconformist lifestyles were all threads in the weave of his nascent worldview. The descriptions of ongoing culture wars between disparate groups of Diggers (agrarian libertarian dissidents, revived by Pennick in local form), Situationists, Dadaists and various other fringe groups are particularly entertaining, as are the titles of the endless periodicals / fanzines published and circulated throughout Cambridge’s cultural underground: Braingrader, Free England, Tribute to Moloch, Hash, Gas, Period, Omphalos, Bloody Women, Dream, Burp, Fred, Flash, Really, Dr Organ, Meat, Warp, Friday and Nitelite!

For me, one hilarious passage sums up the febrile, hallucinogenic, fragmented and heterodox nature of the times, when Pennick offered to set up and run a Cambridge meeting space for people of any spiritual path, sponsored by the London-based magazine Gandalf’s Garden:

So once a week I ran the Gandalf’s Garden Seed Centre, which attracted about twenty people. They included Sannyasins, Buddhists, astrologers, communards and Sufis… But the Sufis were intent on taking over. I argued with them that recruitment to their belief system was not the function of a Gandalf’s Garden Seed Centre… [but] they became increasingly heavy towards me, and I feared that something unfortunate would occur – what in those days would have been called a ‘bad scene’.

It was from this vibrant, underground, alternative culture and its associated publishing arms that the earth mysteries movement emerged, along with its journals: The Ley Hunter, Arcana, Lantern, Albion and others. This intensely creative, inspired decade from the early 70s to the early 80s saw the likes of Paul Devereux, John Michell, Michael Behrend, Paul Screeton, Tony Roberts, Ronald Hutton et al promulgate a huge range of ideas that, combined, became powerful medicine. Situated at the crossroads of folklore studies, esoteric spirituality, DIY archaeology and New Age philosophy, this geomantic elixir has seeped into the occulture of the 21st century and, ironically, resurfaced in the present wave of fanzines such as Weird Walk, Shuck, Hellebore, Eva, Fiddler’s Green and others.

Yet towards the end of this fertile period, Pennick’s disillusionment with the inevitable infighting and factionalism is evident, as is his scepticism towards the many theories associated with ley enigmas and earth mysteries. Instead, he turns his attention to the Elder Ways – the ancestral traditions and Nameless Art of Britain, England and East Anglia. 1995 marked my first encounter with Pennick’s work when I obtained a copy of Secrets of East Anglian Magic. As a bred-and-born Suffolker, I was delighted to discover that East Anglia possessed its own magickal traditions, many of which I was completely ignorant of, but some I had certainly intuited. Thereafter Pennick became a significant influence on my magickal life and practice.

Wyrd Times continues with further digressions into the Futhark, music, art, crafts and Pennick’s travels abroad. It is without doubt an exhaustive document of his life’s works – possibly too exhaustive. Much of its more granular detail will be of interest to specialists rather than the general reader. Yet the book deserves the widest possible audience. As an account of one man’s spiritual awakening and evolution, and his rites-of-passage through the most pivotal decade of the 20th century, it is nothing less than fascinating. Add to this his devout heathenism, his status as an initiator and influencer in modern British occultism, his prodigious written output – all of these elevate the book to the status of ‘essential reading.’ If I have one criticism, it is that more insight would have been welcomed; more of the ‘why’ alongside the ‘what’. Pennick shows us pretty much everything, but reveals only occasionally the private voice of his inner life.

The book ends by documenting a period of ill health: heart attacks, heart failure and pace makers. It is a salutary reminder of the inevitability of death, but also of its potentia – the onward journey into other realms, other forms, other lives. Pennick acknowledges his mortality without bathos. And Wyrd Times is evidence of a life lived according to its true will, seemingly free of regret. In contrast to contemporary occultism’s obsession with compartmentalisation, labelling and tribalism, Pennick notes how, in the late 60s and early 70s there was no distinction between radical politics, the struggle for rights, the environment, art, folklore and history, alternative culture and esoteric spirituality. Because of this he was able to flourish and ultimately become the ‘pagan renaissance man’ of the book’s title. May we all enjoy such freedoms on our journeys.