One unexpected aspect of Val Thomas’s book ‘Of Chalk & Flint’ is this: it provides an interesting insight into the activities of a community of magickal practitioners. Not necessarily in terms of an organised coven, secret confraternity or structured school, but a loose group of folk who come together at key points in the year to perform ritual and engage with the land and its spiritual denizens. Val quite often prefers ‘we’ over the personal pronoun ‘I’ and there’s a chatty, inclusive tone to the writing. Certain individuals even have an entry in the book under ‘A Treasury of Talent’ to give voice to their own experiences and journeys. For those readers who are solitary practitioners, these insights reveal the benefits of community, from praxis to an enhanced social life. One might even approach the book as a blueprint for this kind of self-organising, democratic model.

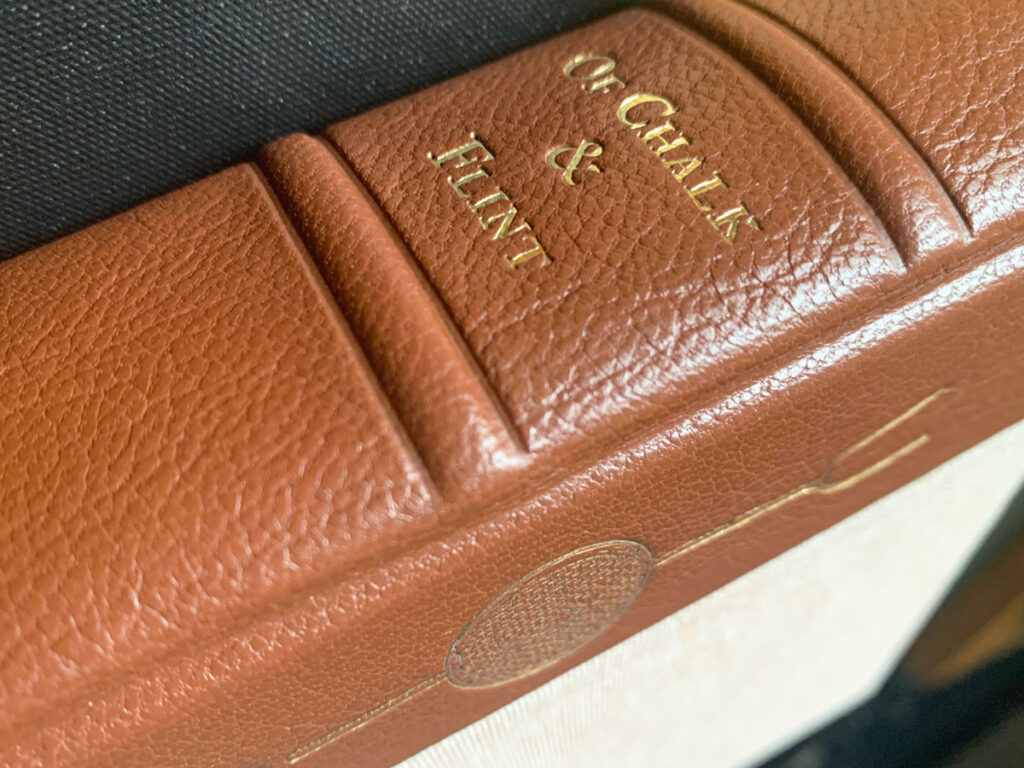

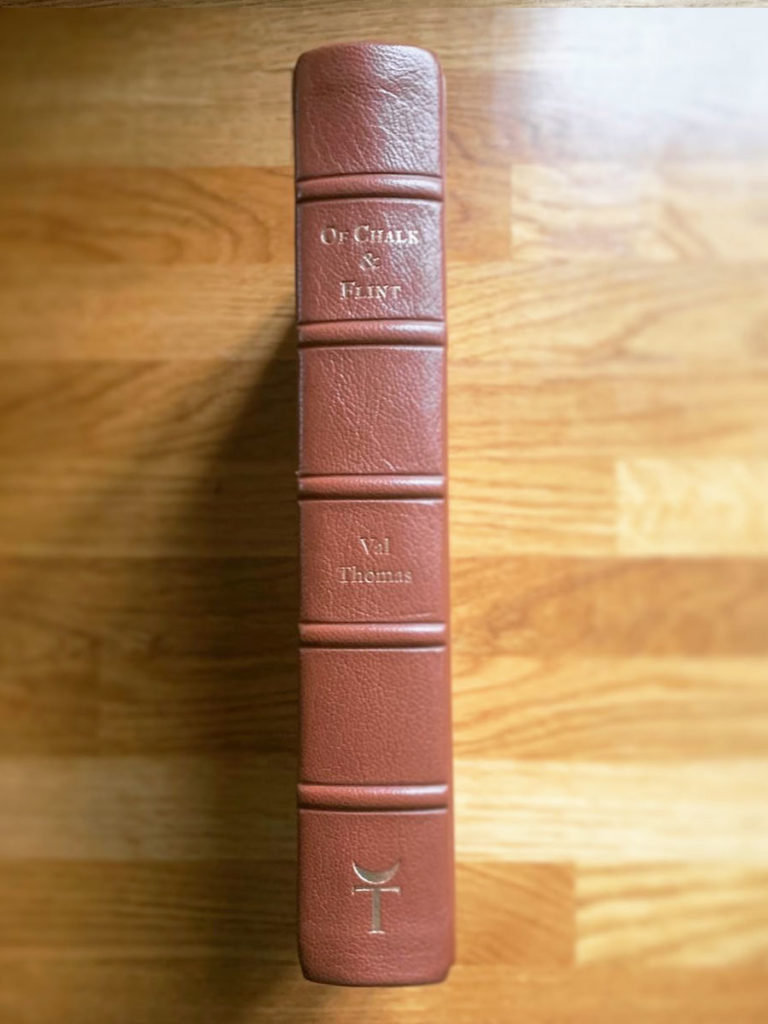

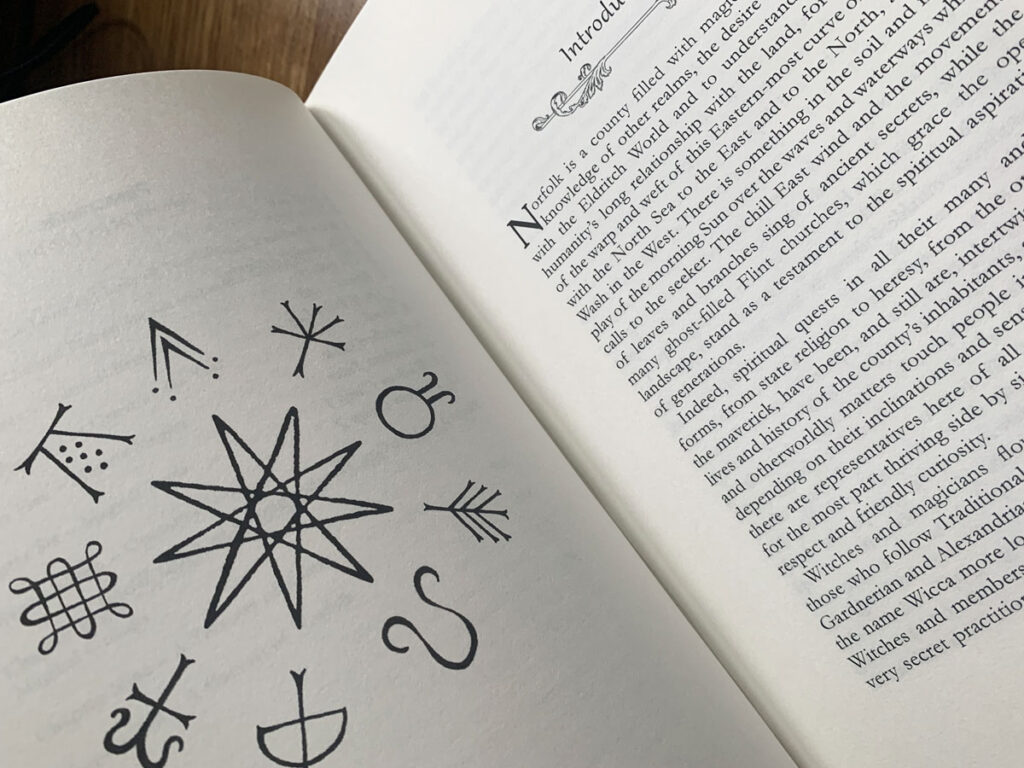

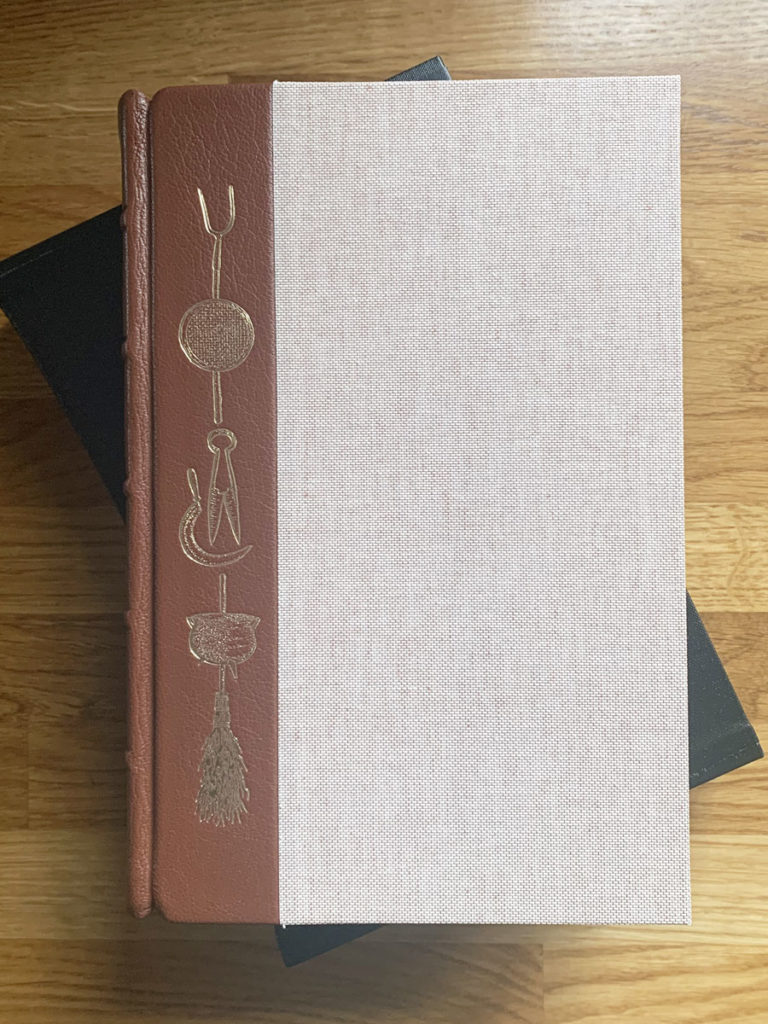

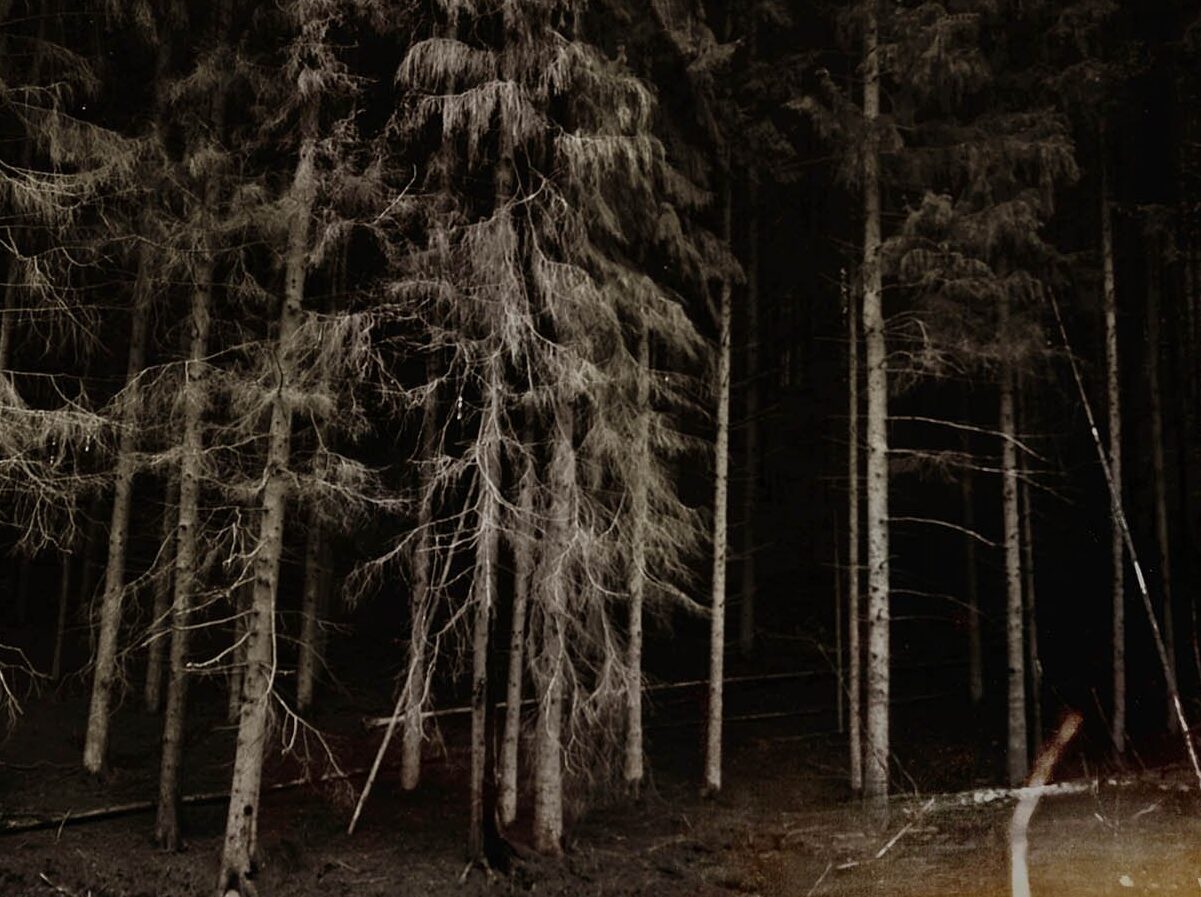

The book as an artefact reflects its contents. Bound in tactile oatmeal-coloured cloth and one-quarter brown leather (fine edition), it emanates good-naturedness and earthy wisdom. Nigel Pennick refers to East Anglian witchcraft as ‘The Nameless Art’ and Val similarly describes the Norfolk path as ‘The Nameless Tradition.’ The book is as much a love-letter to her adopted county as a document of its long magickal heritage, and this is essential: the reader cannot begin to understand the Craft, which is of the Land, unless the Land itself is understood in some way. There’s no substitute for actually experiencing it first-hand, but Val does a good job of evoking its wide-open vistas, narrow lanes and sacred places. The old kingdom of East Anglia was once described as water-girdled, isolated by the North Sea to the north and east, the Fens to the west and the River Stour to the south. It is this remoteness that gives Norfolk a special quality.

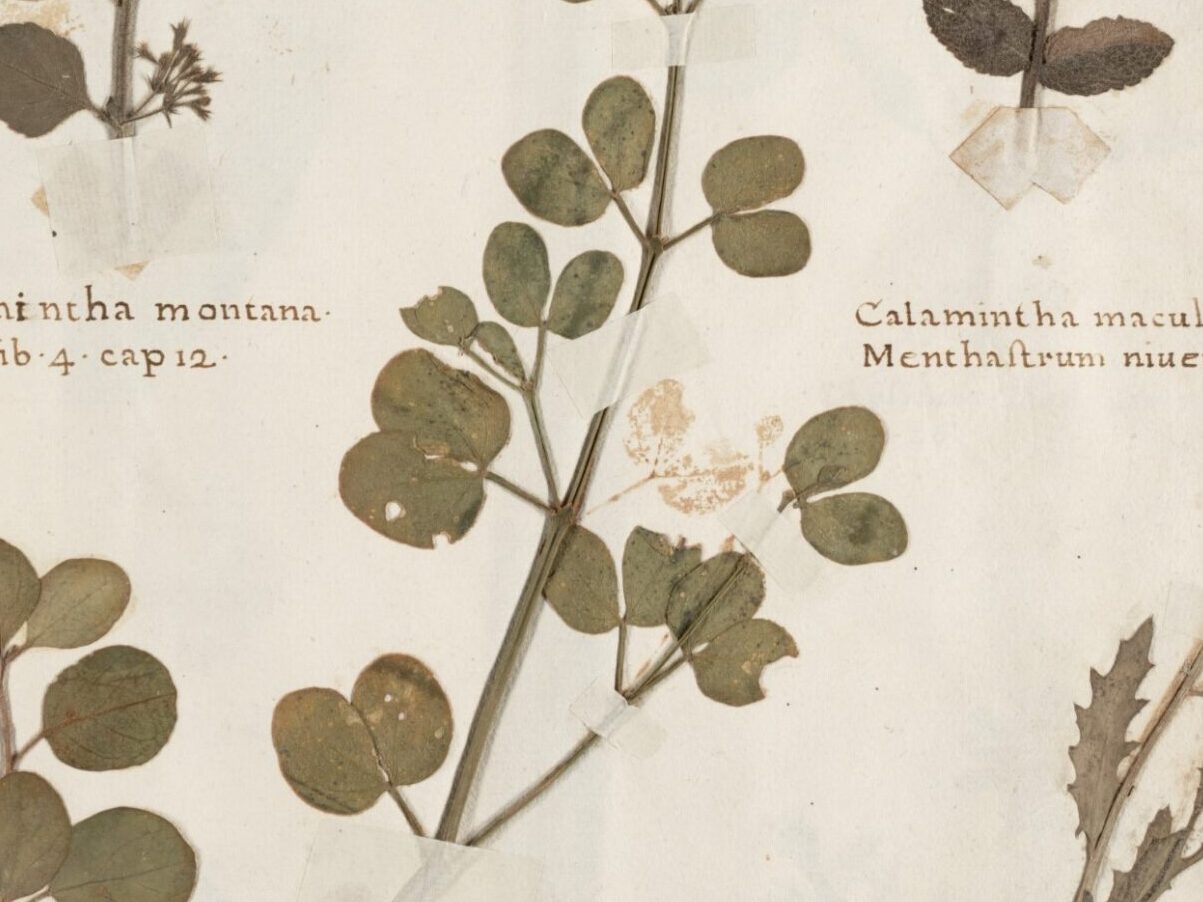

The two primary deities of The Nameless Tradition are the Grey Lord of the Flint and the Lady of the Chalk – embodiments of the chief numen of the county. These are accompanied by a pantheon of saints, fey folk, historical figures, mythological beings, flora and fauna. The ritual year is tied to the seasonal agrarian cycles; its tides and its practices are thoroughly documented, with a bias towards plant-lore, as one would expect from a practicing herbalist. There are also comprehensive chapters on magical tools and operative magic, all accompanied by personal anecdotes and interesting asides.

It’s almost become a cliche to think of English witchcraft only in terms of west-country traditions. In fact, these Holy Islands are entirely steeped in otherwordly mists. Yet it is true to say that its extremities are especially numinous; both east and west give a sense of withdrawal, of leaning away from the centre. The two traditions have their differences: the east sees the sun first; its topography is relatively flat; farming is agrarian; the heritage is Norse and Anglo-Saxon. The west sees the sun last, is largely hilly and pastoral with a Celtic heritage. Yet as Val makes clear, the two are linked – by telluric and magickal currents, and by the exchange of ideas. Most importantly, both are living traditions that continue to evolve in tandem.

In Val’s paen to Norfolk we have the completion of an East Anglian triad, including Nigel Pennick’s ‘Secrets of East Anglian Magic’ representing Cambridgeshire and Nigel G. Pearson’s ‘The Devil’s Plantation’ for Suffolk. These three books embody the traditions of the three counties of the old kingdom, the three crowns of East Anglia. Anyone with a serious interest in East Anglian magick would do well to include them in their library.